Osnovni delci Cirkulacije 2 na festivalu IZIS Koper

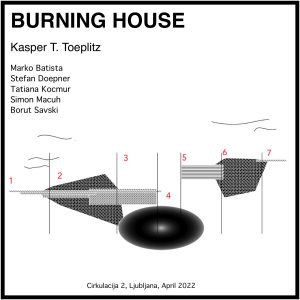

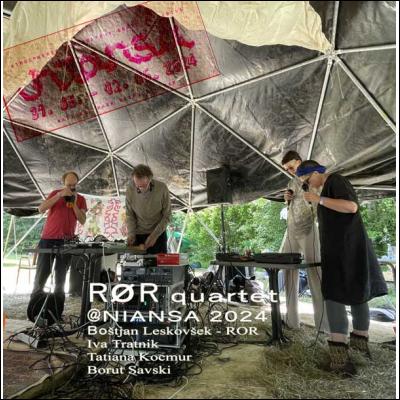

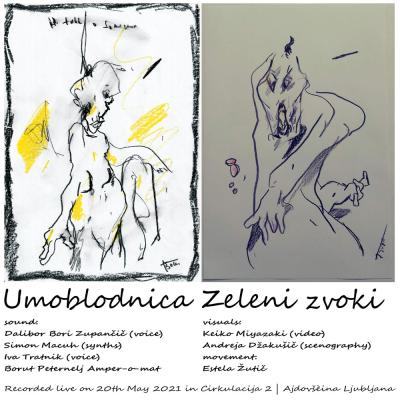

Published on October 2nd, 2023Be informed and invited to the IZIS 11 festival in Koper, with the participation of elementary particles of Cirkulacija 2 (Marko Batista, Tatiana Kocmur, Borut Savski, Stefan Doepner, Simon Svetlik, Vlado Repnik, Sanja Simić and name:). Together with other particles, the festival will open on Friday, October 6, 2023 at 20:00 at the Libertas Warehouse. Lasts until 22nd October 2023.

Elementary particles https://festival-izis.org/en/elementary-particles/

“The kingdom’s limits are fragile.” after Michel Houellebecq, Atomised

“The kingdom’s limits are fragile.” after Michel Houellebecq, Atomised

“Between 1900 and 1920, Einstein, Bohr and their contemporaries developed a number of ingenious models which attempted to reconcile this idea with previous theories. It was not until the 1920s that it became apparent that such attempts were futile. Niels Bohr’s claim to be the founder of quantum mechanics rests less on his own discoveries than on the extraordinary atmosphere of creativity and intellectual openness he fostered around him. The Institute of Physics, which Bohr founded in Copenhagen in 1919, welcomed the cream of young European physicists. Heisenberg, Pauli and Born served their apprenticeships there. Though some years their senior, Bohr would spend hours talking through their hypotheses in detail. He was perceptive and good humoured, but extremely rigorous. However, if Bohr tolerated no laxity in his students’ experiments, he did not think any new idea foolish a priori; no concept was so established that it could not be challenged. He liked to invite his students to his country house in Tisvilde, where he also welcomed politicians, artists and scientists from other fields. Their conversations ranged easily from philosophy to physics, history to art, from religion to everyday life. Nothing comparable had happened since the days of the Greek philosophers.” (Michel Houellebecq, Atomised, p. 15–16, trans. Frank Wynne.)

11th IZIS, with the title Elementary Particles, soon had us discussing quantum mechanics. The theory which dismantled the classic image of the atom and pushed the Italian physicist Carlo Rovelli to declare in his book Helgoland (2020) that: “The classical vision of the world is no longer a confirmed hallucination.” Even though the development of the theory was a group effort, we can perhaps establish the exact date, 7. 6. 1925, when its fundamental insight was brought to light. Werner Heisenberg reports on it from the island Helgoland: “It was almost three o’clock in the morning before the final result of my computations lay before me, […] and I could no longer doubt the mathematical consistency and coherence of the kind of quantum mechanics to which my calculations pointed. At first, I was deeply alarmed. I had the feeling that, through the surface of atomic phenomena, I was looking at a strangely beautiful interior, and felt almost giddy at the thought that I now had to probe this wealth of mathematical structures nature had so generously spread out before me.” (Heisenberg, Physics and Beyond)

The Copenhagen interpretation assumes the validity of both Newtonian and quantum mechanics, while the border between them is not clearly defined, and especially on the quantum level strange happenings abound: sometimes there are waves and sometimes particles, all depending on whether there is an observer. Even today physicists cannot unambiguously explain this with words. Sean Connell, the proponent of the Many worlds interpretation – as opposed to the Copenhagen one – tells us, that: “With equations it’s crystal clear, with words is hard.”

“Heisenberg imagined that electrons do not always exist. They only exist when someone or something watches them, or better, when they are interacting with something else. […] Einstein did not want to relent on what was for him the key issue: that there was an objective reality independent of whoever interacts with whatever, and remained convinced that things could not be as strange as it proposed – that ‘behind’ it there must be a further, more reasonable explanation. A century later we are at the same point. The equations of quantum mechanics and their consequences are used daily in widely varying fields: by physicists, engineers, chemists and biologists. They are extremely useful in all contemporary technology. Yet they remain mysterious. For they do not describe what happens to a physical system, but only how a physical system affects another physical system. What does this mean? That the essential reality of a system is indescribable? Does it mean that we only lack a piece of the puzzle? Or does it mean, as it seems to me, that we must accept the idea that reality is only interaction?” (Rovelli, Seven Brief Lessons on Physics)

At this year’s IZIS we tried to acknowledge and accept – as much as we could – Rovelli’s relational interpretation. To make the Libertas exhibition space display the highest possible degree of interconnection with what is exhibited. The curatorial work with the authors. The limits of personhood with authorship. And above all else: the creative process of each of us with the inner core of necessity that drives us. And after all these years that have passed since the youthful aspirations of the first IZIS – if it is true that the elementary particle is the relationship – “which was a tangle of intellectual tumult, free spirit and friendship,” to verify if this statement still holds true.

“‘If it passes, it means it was not true love.’ In this case, why not? Is our experience such that only this feeling is permanent, while the other is not? Or we use an image: we experience love through its inner structure, which is not revealed by direct feeling. And yet this image matters to us. Love, that which matters, is not a feeling but something deeper, which is only expressed in the feeling. We have the word ‘love’ and we use this title for that which is most important.” (Wittgenstein in: Simoniti, On Declarations of Love)

We dedicate IZIS to Brane Grgurovič, whose Fuck Off Illusion brought us to Libertas for the first time. He was fond of saying that the photons have told him and he died on August 1st, 2023. You are invited: we hope that “by using these words, we can learn their limitations” (Heisenberg) together.

Karlo Hmeljak

Translated by Jasmin B. Frelih